It is a recurring biblical pattern. Time and again it is the woman who gets and it, and the man who does not.

It started with Eve.

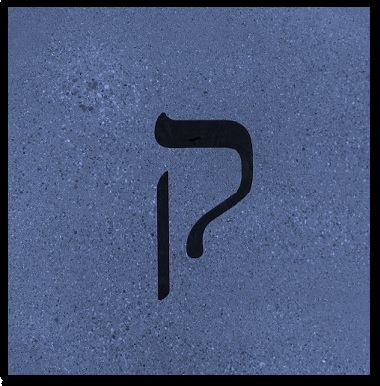

For millennia people have blamed Eve for the so-called fall of man, but really she is the heroine of the elevation of humanity (see my blog essay, The Pastor’s Convention). It was she not Adam who perceived that life in Eden–while idyllic–was sterile and essentially without meaning. It was she who saw (Genesis 3:6) “ונחמד העץ להשכיל the tree of knowledge was desirable as a source of wisdom, so she took of its fruit and ate.”

Rebekah

Later in Genesis, Rebekah (Genesis 25:19 ff) has far clearer sense of God’s will than her husband Isaac. She is the far stronger character as well.

Tamar

Judah–the reason we call ourselves Jews–transforms from a villain into a hero only after he matriculates at ”the Tamar Yeshiva of Timnah.” (See Genesis 38) At his “graduation ceremony” Judah acknowledges, “She has been more righteous than I.” (Genesis 38:26)

Moses is unquestionably the Bible’s most important figure, but he owes his entire career to the vital intervention of no fewer than six women. (See my essay, Six Women Made Passover Possible)

Shifrah and Puah

The first two are the wonderful midwives, whose actions rebut across the millennia, the cowardly Nazi war criminals who tried to excuse themselves by saying “I had no choice. I was just following orders. “ Shifrah and Puah received orders too, from their boss, their king, the most powerful man in the world who was worshipped as a god. “When you help the Hebrew women give birth and you see it is a boy, kill it.” (Exodus 1:16)

Shiphrah and Puah teach us all that we must never just follow orders. We must interpose our conscience and our human ability to determine what is right and what is wrong before we follow any orders.

Yocheved

Moses’ mother Yocheved refuses to submit to Pharaoh’s vile decree that every Hebrew baby boy be drowned. In desperation she floats him in a watertight basket down the Nile.

Miriam

Miriam, his sister, watches and with perfect timing runs up to Pharaoh’s daughter when she finds the baby and offers to provide a nursemaid for him.

Our Sages enhance Miriam’s role. A Talmudic tale (B.Sotah 12A) teaches that Amram, Moses’ father, was the leader of the Hebrew laves at that time. In order to avoid the pain of Pharaoh’s cruel decree, Amram ordered all the Hebrew men to divorce their wives, but Miriam convinced her father not to give in to Egyptian oppression.

Pharaoh’s Daughter

Then we come to the amazing act of heroism of Pharaoh’s daughter.By all logic as a “good” daughter, loyal subject of her King and worshipper like the Egyptians of her father as a god, she would have simply tipped Moses’ basket over and drowned him. But she answered to what she rightly perceived was a higher authority. Pharaoh’s daughter is unnamed in the Bible, but the Sages call her, “Bityah”, “”the daughter of the Almighty.” (Leviticus Rabbah 1:3)

Moses’ wife Zipporah also saves his life.

There is a strange but interesting passage in Exodus 4:24-26 that tells of Zipporah circumcising their son after Moses had neglected to do so. It is a passage the rabbis could have interpreted any way they wish, but the rabbis (Shmot Rabbah 5:8) credit Zipporah with saving Moses life by her quick thinking and decisive action!

The pattern of women who are savvier than males continues in the biblical books after the Torah.

In the Judges (Chapter 13) an angel announces to Manoah and his wife that she will bear a son, Samson. Manoah completely misunderstands the angel’s message and thinks they will die. Manoah’s wife must reassure him that is not the case.

After Moses, Samuel is arguably the Hebrew Bible’s most important figure. When his mother Hannah prays to give birth to a son. Eli, the clueless high priest at Shiloh thinks she is drunk. Of course she is not, and God grants her prayer. (I Samuel 1:10-20)

Deborah, Yael, Ruth, Esther, Vashti (yes, Vashti, see my essay The Adult Issues of Purim) are other biblical women who are smarter and greater than their male counterparts. We must tell their stories of over and over. May their examples inspire us to struggle relentlessly for gender equality in Judaism and in our world.