Of the 150 chapters that comprise our people’s first and greatest prayer book, the biblical book of Psalms, only one of those chapters is attributed to the greatest Jew of all—Moses. That is Psalm 90, which contains humanity’s fervent appeal to God: “Establish for us the work of our hands!”

Moses’s appeal is not just for temporal prosperity, as some might interpret it. It is much grander than that. He is saying, “Let me know that my life has meaning beyond the days I have spent on earth. Let me be sure, O God, that the years of my earthly journey were not in vain. Let me know that in some way I live on.”

We express that same hope every time we visit a cemetery and every time we place a monument marker at the grave of a loved one.

One of the questions people ask me most frequently is, “Rabbi, what really happens to me after I die? Do we Jews believe in life after death? Do we believe in heaven or hell?”

The simple answer to the question is, “Yes! We do!” Rabbinic literature speaks of olam ha-ba, “the world to come,” as a place where the righteous receive reward and the wicked are appropriately punished.

“Why then,” the questioner retorts, “do we hear so little of this in Jewish life while it is at the center of every Christian service or funeral that I attend?”

The answer points to a significant and honest difference between Christianity and Judaism as they developed. Our daughter religion was very much centered on the afterlife. Achieving salvation after death was the primary goal of living as classical Christianity understood it. If one believed in the saving power of the life, death on the cross, resurrection, and ascension to heaven of Jesus as the Christ (which is simply a Greek word for “Messiah”), then one’s eternal salvation and reward were assured.

For Jews, questions of afterlife have always been much less central. Our primary focus has always been on this life. Our primary goal in living is not to attain salvation in the world beyond, but to make the world in which we live as good a place as we possibly can.

In recent decades, we Jews—Reform Jews in particular—have so submerged mention of the afterlife that many Jews frame their question to me as an assumption. They say, “We don’t believe in life after death. Do we, Rabbi?”

Again, I would assert, “Yes, we do!” For Jews, attaining the reward in olam ha-ba (“the world to come”) does not depend on what we believe. It depends on how we act. It does not matter what we believe or do not believe about God. It is a matter of how we live our lives.

We are also very fuzzy on the details. Our focus has primarily been “Live your life here on earth as well as you can. And the afterlife, whatever it will be, will take care of itself.”

Still, our hearts yearn for a more specific answer to the question “What happens after I die?” I shall share mine with you. I divide my response into two parts: what I hope and what I know.

I hope, and in my heart I believe, that good people receive, in some way, rewards from God in a realm beyond the grave. I hope that they are reunited with loved ones and live on with them in a realm free of the pain and debilitation that might have marked the latter stages of their earthly life.

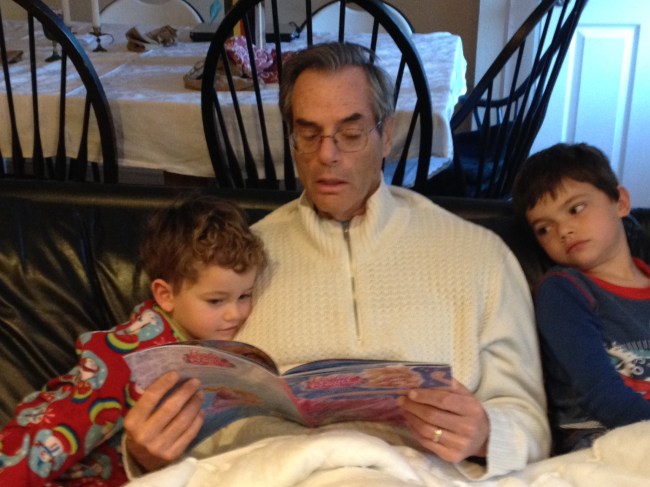

Speaking personally, my father died at age fifty-seven; and my mother, who never remarried, died at age eighty-eight. She was a widow for more years than she was married. My fondest hope since her death is that they are together again, enjoying the things they enjoyed on earth and as much in love with each other as the day they stood beneath the chuppah to unite their lives.

I hope, pray, and even trust that they are young, strong, and vigorous—not weak and frail as they each were before they died. I hope and pray also that, in some indescribable way, they are able to feel and share the joy of the happy events that our family has shared since they left us.

I cannot of course prove that any of this is true. Yet there is warrant for these hopes in the annals of Jewish tradition. There are enough wonderful stories attesting to an eternal reward for goodness in the world beyond to allow me to cling tenaciously to my hope and belief.

Beyond what I merely hope, though, there is an aspect of afterlife of which I am absolutely sure. Our loved ones live on in our memories, and those memories can surely inspire us to lead better lives.

At the beginning of Noah Gordon’s marvelous novel The Rabbi, the protagonist, Rabbi Michael Kind, thinks of his beloved grandfather who died when he was a teenager and recalls a Jewish legend that teaches, “When the living think of the dead, the dead who are in paradise know they are loved, and they rejoice.” As I said, I hope but certainly cannot prove that it is true. But I can reformulate that legend into a statement that is unimpeachable: When I think of my dear ones, I know that I have been loved, and I rejoice. I rejoice in and try to live up to the life lessons they taught me. I rejoice in the memories of happy times I shared with them. I rejoice in the knowledge that I am a better person because of them.

Not long ago, I decided to dedicate two seats in the rear of our sanctuary at Congregation Beth Israel in memory of my parents. I chose those seats because they mark the exact spot in my boyhood synagogue where my parents’ reserved High Holy Day seats were located in the sanctuary of Temple Sharey Tefilo in East Orange, NJ, where I grew up.

Every time I look at them, it is easy to imagine them sitting there. During silent prayers and when the cantor sings, my heart overflows with wonderfully inspiring memories.

On Yom Kippur and on the last day of our Sukkot, Passover and Shavuot festivals, we say Yizkor prayers for the same purpose: to draw inspiration from the wonderful memories that fill our hearts and minds when we think of those whom we have loved. We long for them, and we want to be worthy of them. The acute presence of their absence reminds us that life is finite and calls to us to make each day count in living up to their ideals and doing what we can to make the world a better place.

I believe we can—if we listen—hear them call to us as God called to Abraham in establishing the sacred covenant of our faith: Be a blessing! Study and follow God’s instruction! Practice and teach those you love to practice righteousness and justice!

And then when we turn their words into our actions, we know—we absolutely know—that our loved ones are immortal and that they live on in a very real and special way.